For decades, we, as footwear consumers and users, have been told that we need plenty of padding in our shoes and under our feet to help boost comfort and buffer the forces on our bodies that occur during standing, walking, running, and jumping. Like many things in the health arena, this information has become common knowledge and accepted as fact. Shoe industry bigwigs along with countless healthcare professionals have championed this idea and instructed customers and patients to look for a high degree of padding or cushioning when selecting footwear, especially athletic footwear. Perhaps not surprisingly, the current ethos in the athletic shoe industry is to embrace padding and all its purported benefits, even going so far as to suggest that the so-called “maximalist” shoes now available are the next step in the evolution of optimal shoe form and function.

The lens through which we at Natural Footgear view footwear leads us to a very different conclusion about what constitutes truly foot-healthy footwear. This article is our attempt to debunk the idea that excessive shoe cushioning is in any way advantageous, and that it may, in fact, be detrimental to immediate and long-term foot and lower extremity health for many people. As always, we hope to cut through industry myths and provide you with the best possible information to make informed choices. Are we anti-cushioning? No, not per se; there are certain circumstances where some shoe padding may be helpful. What we do take issue with is the notion that more padding necessarily means a safer and healthier shoe for all. But more on this in just a bit.

The Myth

One of the main points we want to establish in this article is that there are a lot of misconceptions out there about shoe cushioning. The prevailing idea behind shoe cushioning is that a greater amount of padding under the foot will help reduce the impact forces on the body’s joints and tissues during weight-bearing activity. Intuitively, this may seem like a reasonable claim, given that we’ve been told for years that we need cushioning to protect our joints and soft tissues from damage. Indeed, it’s an easy concept to wrap our minds around. What you may be surprised to learn, however, is that physics and research do not support this claim. In fact, the more cushioning a shoe possesses, the harder and more damaging on our joints it may be.

The Physics

To understand why this is so, it’s important to understand the physics of collisions. To start with, the net force acting on an object is:

With a body that has one foot in contact with the ground, there are two vertical forces acting on the body, which are the ground pushing up, traditionally referred to as the Normal Force, which I'll write as N (normal in this context meaning perpendicular to the surface) and the force of gravity pulling down, often expressed as mg, or mass times 9.8 meters per second squared. So we have:

The acceleration is defined as change in velocity divided by time, so using vf as final velocity and vi as initial velocity, and doing some rearranging, we can write this equation as:

So what changes when someone goes from a thickly cushioned shoe to a minimalist shoe or even to being completely barefoot? The real expert in this realm is Professor Daniel Lieberman at Harvard, who has done some really nice studies on impact forces using force plates so that the forces of running shod versus barefoot can actually be quantified. But here is the essence of the argument: With shoe cushioning, our sense of what is going on is dulled (see Cushioning Issue #1 below for additional thoughts on this topic), and we tend to run with a certain gait—a gait that involves more up and down bouncing as well as feet that reach out more and strike first with the heel during the landing phase of walking or running.

There may be small fluctuations in the time that the foot is in contact with the ground between shod heel strikers and barefoot or minimalist midfoot strikers, which would affect the Normal Force, but the real key here is that the shod, cushioned gait makes both the initial downward velocity and the final upward velocity larger (Note: The above equation is written using the convention that up is positive and down is negative, so the vf is a positive number and the vi is a negative one—meaning when both numbers get larger, the difference between them gets larger). This results in a larger Normal Force, or, in other words, more force that the foot and rest of the body has to deal with. However, when running barefoot or in minimalist footwear, we tend to change our gait. We bounce less, and we tend to make the foot strike happen more underneath our bodies instead of out front. So, instead of landing hard on the heel like we do in cushioned shoes, we control the impact better in minimalist shoes or with our bare feet and make the difference between vf and vi less, thereby reducing the overall force on our feet and bodies.

Below are a couple of examples using real numbers in the force equation to illustrate the above points. For our examples below involving runners, let’s set mass (m) equal to 50 kg. The acceleration of gravity (g) is a constant at 9.8 m/s2. Let’s set the change in vertical velocity (vf - vi) equal to 8 m/s for cushioned shoes and 6 m/s for minimalist shoes or bare feet. For the impact duration, let’s use a value of 0.3 seconds for both cushioned shoes and minimalist shoes.

Note: To better understand the rationale behind the selection of these numbers, please scroll to the very bottom of this article, to the “Appendix: Understanding the Numbers” section, for a more detailed explanation.

Example #1: Force experienced by a runner in cushioned shoes:

Example #2: Force experienced by a runner in minimalist shoes (or with bare feet):

For the sake of comparison, a 50 kg person weighs 490 N in metric units of force, so that first number (for cushioned shoes) is about 3.7 times bodyweight whereas the second number (for minimalist shoes or bare feet) is only about 3.0 times bodyweight. Add that difference up over miles and days, months, and years of running and walking, and you can see why keeping shoe padding to a minimum makes such a huge difference.

It’s true that the physics of collisions is much more complex and detailed than what’s shown above (for example, we’re treating all of the person’s mass as moving up and down at the same speed; in reality, it’s more complicated as the torso obviously doesn't move up and down at the same speed as the feet do), but the equation does demonstrate the point that using cushioned shoes actually equates to greater forces on lower extremity joints and tissues, not less.

Note: If we wanted to get more technical in our calculations, we would take into consideration the fact that the ground reaction force is made up of several vectors in different directions. This would be a more rigorous way of explaining the force of the ground on the foot. The equation I used above captures only purely vertical force, which does make the point about vertical velocity changes in the foot being different between a heavily shod runner and a minimally shod or barefoot runner, but it leaves out the motion of the runner or walker and the foot itself in relation to the moving ground. Landing and takeoff angle would also be a factor here, as would the way in which force moves through the foot. And so on. The point is, though, a fancier model would still contain the key points demonstrated in the above examples.

Cushioning Issue #1: Joint Impact

What’s true of excessive shoe cushioning is that it’s highly deceptive: It makes us think we’re reducing joint impact because it feels that way, but in fact it’s just reducing the sensation of the impact. According to the laws of physics (as demonstrated above), the impact forces on our joints and tissues actually increase in more highly cushioned shoes. Excessive shoe cushioning can be hugely detrimental to our joints and tissues because it allows us to be sloppy with our footfalls or foot placement, and it allows us to slap our feet down with tremendous force without any perceived consequences.

When we fail to place our feet just right (including in the proper alignment relative to the ground), our weight distribution gets thrown off. The heels, toes, and arches are not able to properly absorb impact and distribute body weight. This can have negative implications for our feet, ankles, knees, back, and so on, all the way up the kinetic chain. By contrast, when we’re barefoot or wearing only thin-soled, flexible footwear, our feet and bodies can feel everything about the ground and what’s happening in our lower extremities. Footfalls tend to be gentler and more mindful, seeking out the smoothest path over which to move forward, and this can have a huge effect on the well-being of our joints and tissues.

Also, doing high-impact activities in shoes with no or only minimal cushioning can, in some cases, feel uncomfortable, but this isn’t necessarily a bad thing because it encourages a reassessment of how we’re performing an activity. Without shoes, landing on the heel can be painful and may result in larger than necessary collision forces. What tends to happen in barefoot people or people who adopt minimalist footwear is that, over time, they will actually develop the ability to move (walk, run, jump, etc.) in a less jarring way. Many people who use minimalist footwear or who go barefoot tend to spread their toes before striking the ground, landing first on the lateral (or outside) aspect of the ball of the foot and then rolling across the ball of the foot until the toe-off phase of gait, in which the big toe leaves the ground last. This footfall pattern, which also incorporates a foot strike that occurs more directly beneath the body's center of mass (instead of in front of it), helps reduce impact forces during the landing phase of gait.

So, interestingly, and perhaps unintuitively, often the best way for us to reduce joint impact is to reduce shoe cushioning. That said, this approach does require some time, patience, and care. And it tends to work best when our toes are splayed (ideally enabled by Correct Toes) and placed flat on the ground or on a completely flat sole, where each of our toes can bear their fair share of the weight. This development also tends to happen naturally; our bodies figure it out based on the strong tactile and proprioceptive feedback they experience in the minimally shod state.

Helpful Exercise: One illuminating exercise you can perform to observe the difference in impact forces between cushioned and minimalist shoes is to plug your ears and then go running, first in cushioned shoes, then in minimalist shoes. You should notice quite a difference in your ears right away, mostly in terms of the jolting and jarring forces your body experiences while running in cushioned shoes.

Cushioning Issue #2: Effort Expended

Another aspect of shoe cushioning that’s often overlooked is the fact that cushioned soles actually force us to do more work with each footfall. The greater the cushioning or sponginess in a given shoe, the less efficiently force is transferred between the foot (the big toe, really) and the ground. Energy that would otherwise go into propulsion is dispersed throughout the shoe’s padding and wasted. It’s a similar effect (though obviously less extreme) to running in sand. In people who ambulate in bare feet or in minimalist footwear, a maximum amount of propulsive energy is transferred between the foot and the ground during the toe-off phase of gait, and considerably less energy is wasted with each step or stride.

Cushioning Issue #3: Foot Muscle Atrophy & Arch Effects

Despite the fact that most conventional shoes, especially athletic shoes, possess springy cushioning under the foot, the relative thickness of the soles translates into greater sole rigidity, which can have detrimental effects on foot muscle strength and arch integrity. As has been said elsewhere on this site and around the web, wearing thickly-cushioned, rigid-soled footwear is like putting your foot in a cast and expecting it to get stronger. The relative foot immobilization that occurs in thickly padded shoes prevents foot muscles from doing their fair share of the work and allows them to slowly deteriorate, or atrophy, over time. A muscle that is not used regularly will lose its tone and its ability to generate sufficient force, which can have a significant effect on the function of the foot and the rest of the musculoskeletal system.

Shoes that possess no or only minimal padding and no built-in arch support help enable the foot to do what it’s intended to do (i.e., these shoes make the foot stronger, more flexible, and less susceptible to pain and stiffness). One of the first sensations many people experience after switching from conventional footwear with lots of cushioning to minimalist shoes with no or relatively little cushioning is the sensation of enhanced foot strength. Foot muscles that have long been underutilized begin to awaken, and the feeling of enhanced foot strength quickly becomes apparent. Shoes without excessive cushioning and so-called motion-control technology also help restore a strong and healthy medial longitudinal (ML) arch—the principal arch in our feet. I can tell you from personal experience that my own ML arch is now much more pronounced and defined since I adopted minimalist shoes and natural foot health techniques many years ago.

Cushioning Issue #4: Injury Frequency

One of the most frustrating aspects of the shoe cushioning debate is the notion that less cushioning inevitably means more foot and lower extremity injuries. A lot has been made of the class action lawsuit that was brought against Vibram FiveFingers, but the fact that Vibram settled their case does not suggest that minimalist shoes are injurious, only that Vibram may have gone too far in touting the health merits of their unique product. It’s true that injuries can occur when using minimalist footwear, but these injuries tend to be of the more acute (i.e., temporary) variety and most likely occur when users transition too quickly. Some problems, such as Achilles tendon issues, may be a direct result of the structural changes in the foot and ankle caused by conventional footwear worn over many years.

Indeed, conventional shoes make our feet weak, and so it’s likely that many people who experienced injuries using Vibram FiveFingers shoes weren’t ready to jump into this type of ultra minimalist shoe without a sufficient transition period. It could also be that users didn’t understand that the minimal cushioning was supposed to alter their gait, and that the altered gait is what most affects the equation shown earlier in this article and reduces forces on the body.

What’s easy to forget with all of the media attention surrounding Vibram FiveFingers shoes is that conventional footwear with excessive padding has caused literally countless chronic foot and toe problems over many decades, and that almost everyone who wears conventional footwear will experience some sort of significant foot problem at some point in their lives.

A classic study by Robbins and Waked published back in 1997 in the British Journal of Sports Medicine states the following:

Athletic footwear are associated with frequent injury that are thought to result from repetitive impact. No scientific data suggest they protect well. Expensive athletic shoes are deceptively advertised to safeguard well through “cushioning impact” yet account for 123 percent greater injury frequency than the cheapest ones.

The “cheapest ones” referred to above are shoes with the least cushioning and motion-control “technology” built into them. Robbins and Waked drew the following conclusions from their study:

This is the first report to suggest: (1) deceptive advertising of protective devices may represent a public health hazard and may have to be eliminated presumably through regulation; (2) a tendency in humans to be less cautious when using new devices of unknown benefit because of overly positive attitudes associated with new technology and novel devices.

Some may assume that shoes, especially athletic shoes, are designed by engineers or biomechanics experts to optimize movement while maximizing foot comfort and health. But the reality is that the shoe industry is driven by aesthetics, or by what “looks good” on the shelf, and that little attention and resources are devoted to creating truly foot-healthy products. So, the very shoes that are touted to enhance athletic performance and prevent injuries actually hinder performance and cause injuries by altering natural foot form and function as well as gait. Indeed, nature gave us everything we need to ensure lasting foot health and prevent injuries, as evidenced by this passage from a study published by Michael Warburton in the journal Sportscience:

Running barefoot is associated with a substantially lower prevalence of acute injuries of the ankle and chronic injuries of the lower leg in developing countries [...] Laboratory studies show that the energy cost of running is reduced by about 4% when the feet are not shod.

While going barefoot is not for everyone, finding shoes that allow the foot to act like a healthy bare foot inside the shoe is something that almost all of us can do to ensure long-term foot and lower extremity health, especially now that natural footgear exists to enable this foot health behavior.

Cushioning Issue #5: Knee Problems

Another important consideration in the shoe cushioning debate is the effect of footwear on knee health. When we land on our heels (as almost all runners and walkers who wear cushioned shoes do), our arches and ankles can't help as much in managing impact, so our knees and hips have to handle our bodies’ natural shock absorption. However, as mentioned earlier in this article, barefoot or minimally shod runners tend to adopt a gentler, impact-mitigating midfoot strike, allowing the arches and ankles to contribute better to shock absorption. With more joints handling the shock, the forces get more evenly distributed between the lower extremity joints.

The relationship between padded shoes and knee problems (specifically, knee osteoarthritis) has been examined more closely in recent years. Conventional medical wisdom states that the following factors may contribute to knee osteoarthritis: Weight, heredity, gender, age, previous traumatic knee injuries, repetitive stress injuries, participation in contact sports, certain health conditions, nutritional deficiencies, and physical deconditioning.

While many of these factors undoubtedly contribute to an accelerated rate of articular cartilage loss, the role of conventional footwear in the development of knee osteoarthritis is perhaps the single most important factor in the onset of this health problem. Several reliable and credible sources have produced compelling arguments linking the long-term use of conventional footwear (i.e., padded shoes with tapering toe boxes, toe spring, heel elevation, and relatively rigid soles) with the development or worsening of knee osteoarthritis.

A 2006 Rush Medical College study, conducted by Najia Shakoor and Joel A. Block and published in the journal Arthritis and Rheumatism, examined stress loads on the knees of study participants who wore various shoe types and no shoes at all. The researchers state the following:

It appears that patients with medial knee [the inside aspect of the knee] OA [osteoarthritis] undergo significant reductions in joint loads at their knees and hips when walking barefoot compared with when walking in their normal shoes. Since knee OA is mediated in part by aberrant loading, and since excess loading has been shown to be associated with pain and disease progression, these data suggest that modern shoes may exacerbate the abnormal biomechanics of lower extremity OA.

Shakoor and Block conclude that:

Shoes may detrimentally increase loads on the lower extremity joints. Once factors responsible for the differences in loads between with-shoe and barefoot walking are better delineated, modern shoes and walking practices may need to be reevaluated with regard to their effects on the prevalence and progression of OA in our society.

It's my personal belief, and clearly the belief of the researchers above, that a lot of lower extremity osteoarthritis could be avoided if we were more selective and judicious with our footwear choices.

Harnessing the Natural Protective Mechanisms of Feet

Individuals who have gone barefoot or who have worn minimalist footwear their entire lives possess several built-in mechanisms that offer sole protection. The first of these mechanisms is optimal toe splay. Toes that are splayed well apart confer a large degree of protection from the impact forces experienced during weight-bearing activity by spreading the impact forces out over a larger surface area. Conventional shoes force the toes together and elevate the toes above the forefoot, focusing a majority of the impact forces on a much smaller area of the ball of the foot. Correct Toes toe spacers can be worn inside shoes with a sufficiently wide toe box to help restore natural toe splay and disperse impact forces over a larger surface area of the foot.

SHOP CORRECT TOES

Our feet also possess several plantar fat pads (under the toes, ball of foot, and heel) that help naturally absorb impact forces, assuming that these pads are positioned properly. In individuals who have worn conventional footwear for years or decades, the forefoot fat pad that’s intended to provide protection for sensitive ball of foot structures becomes displaced anteriorly (i.e., toward the ends of the toes) due to a shoe design element called toe spring. This displacement leaves ball of foot structures (e.g., nerves, joint capsules, bones, etc.) vulnerable to the large forces incurred by the body during weight-bearing activity and can cause or make worse conditions such as neuromas, capsulitis, and stress fractures.

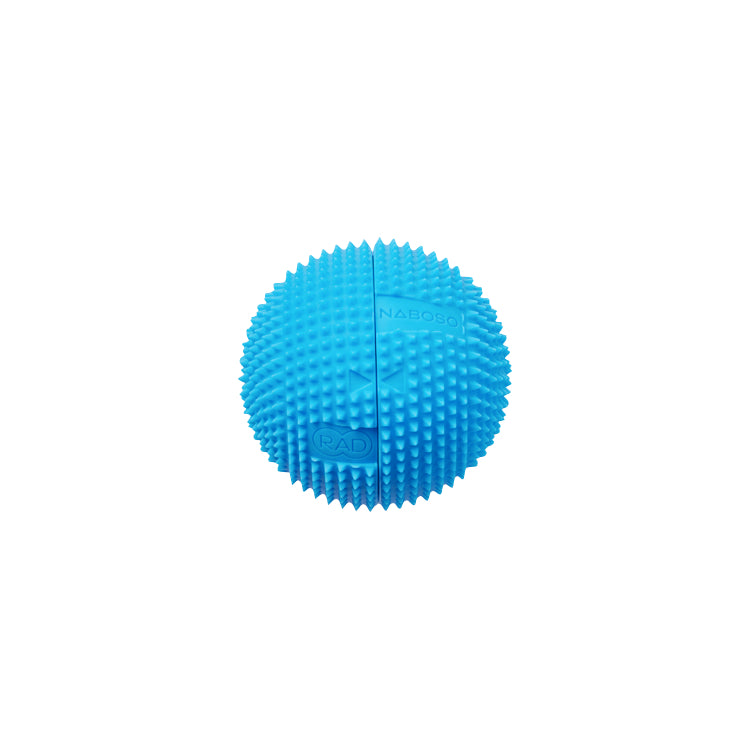

In those transitioning from conventional footwear to minimalist or minimalist-like footwear, three key pieces of footgear can be helpful in eliminating discomfort, restoring fat pad position, or augmenting the natural shock absorbing abilities of the plantar fat pads: Pedag metatarsal pads, Naboso insoles, and Tuli’s heel cups.

SHOP PEDAG MET PADS SHOP NABOSO INSOLES SHOP TULI'S HEEL CUPS

Of all the natural protective mechanisms built into our feet, perhaps the most important is the ML arch. Our foot arches, including the ML arch, are natural shock absorbers and are designed, like arch bridges, to bear an incredible amount of weight. In fact, our foot arches are at their best when they are loaded, as this causes all arch components—bones, ligaments, tendons, and other tissues—to mesh to a greater degree.

Note: Many of the bones in the foot are themselves arch shaped, suggesting that these bones are perfectly designed for bearing weight.

But in order to help stabilize the foot and ankle and absorb shock, the ML arch needs to be on a level and stable support platform. Most conventional shoes, from casual shoes to athletic shoes, possess a spongy or springy sole that elevates the heel above the ball of the foot, which in turn acts to destabilize the main foot arch and reduce its ability to effectively absorb and disperse impact forces. Shoes with minimal cushioning and a completely flat support platform help manage impact forces by enabling natural arch support, strengthening the foot’s arches, and creating a situation of optimal stability in the foot and ankle complex.

Might Some People Benefit from Cushioning?

Some of you reading this article may contend that shoe cushioning is essential for foot comfort. And that may indeed be true, especially for individuals who have experienced some sort of foot trauma. However, it’s likely that most people who rely on conventional shoes with plenty of built-in cushioning for foot comfort have done so for many years, perhaps decades, and that their feet have adapted to the environment in which they've been confined.

Jumping immediately from cushioned shoes to shoes with relatively little cushioning is not necessarily the right thing for everyone. In fact, a slow and measured transition period is extremely important. This article discusses possible ways to transition to more minimalist-like shoes in a safe and stepwise manner and is particularly relevant for people who have long worn conventional footwear. Adopting a transitional shoe—a flat-soled, wide toe box shoe that possesses a moderate degree of cushioning—before a true minimalist shoe is one approach that many people have benefitted from.

Shoe Cushioning: An Impediment to Optimal Foot Health

The intention of this article is to put the role of shoe cushioning into proper perspective and to examine the ultimate value of shoe cushioning as a foot health and injury prevention tool. Hopefully this article has presented a new viewpoint on the utility of shoe cushioning or perhaps confirmed your suspicions about the claims of many shoe manufacturers. In our experience, we have found that shoe cushioning (especially excessive cushioning) is often an impediment to optimal foot health, and that true foot comfort can be achieved, in many cases, by restoring proper foot and toe anatomy and alignment through the use of helpful and unobtrusive natural footgear.

How comfortable a shoe feels is not in itself a good criterion for predicting long-term foot health or even success with a particular shoe. There are a lot of factors to consider when selecting foot-healthy footwear, including making sure that it fits correctly and taking the time to transition properly. When it comes to choosing the best footwear to put on your feet, exercising care and good judgment is always the best policy. To learn more about the best footwear options for you and your unique foot needs, consider speaking with a naturally-minded foot health expert, or check out our foot-healthy footwear options for men or women.

SHOP MEN'S SHOES SHOP WOMEN'S SHOES

Appendix: Understanding the Numbers

In conducting online research for this article, I found several references for the duration of ground contact that suggested 300 milliseconds (or 0.3 seconds) for the average runner, all the way down to 0.2 or even slightly less for more elite runners. This number seemed to be about the same for both shod heel strikers and barefoot midfoot strikers.

In trying to determine accurate values for the change in vertical velocity of the foot between the heavily shod and the minimally shod, other factors needed to be considered, including cadence and the distance traveled by the foot per stride. Allegedly, an average runner has a cadence of 160 strides per minute, getting up to 180 for more experienced runners. An estimation of the vertical distance the foot goes up in one stride is 0.35 m to 0.4 m. If you double that distance (going up plus going back down), multiply by 160, and divide by 60 seconds, you can determine that the average speed of the foot during a stride has to be around 2 m/s.

The tricky part here is that the foot isn't going at a constant speed; it is paused for a moment at the very top as it transitions from going up to coming back down. It’s paused again while in contact with the ground. The simple way to estimate the top speed of the foot is to just double that number, so say 4 m/s on the way down right before impact, and 4 m/s on the way up right after losing contact with the ground. That would give a change in velocity of 8 m/s. Those numbers are based on runners wearing cushioned shoes, so it seems accurate enough to use a value of 6 m/s for minimally shod or barefoot runners.

A very special thank you to physics instructor Peter Peterson and mechatronics engineer Dan Casciato for their kind assistance with various aspects of this article, especially the physics section.

If you look at the foot of a young child, you will notice that his or her toes are spaced well apart. The foot of a young child is naturally designed for optimal balance and gait, and if the foot maintains this shape, optimal stride is preserved through old age: a finding observed in barefoot populations the world over. In industrialized societies, however, people spend a lifetime wearing shoes with...

Read more

If you look at the foot of a young child, you will notice that his or her toes are spaced well apart. The foot of a young child is naturally designed for optimal balance and gait, and if the foot maintains this shape, optimal stride is preserved through old age: a finding observed in barefoot populations the world over. In industrialized societies, however, people spend a lifetime wearing shoes with...

Read more

I would think the greater cushioning would increase the impulse (the exact time it takes for force to transfer from one structure to another) when it first comes into contact with the ground. This would slightly lengthen the value for “t” and it would explain why people “feel less impact” and tend to run harder when they are wearing shoes with lots of cushioning. I don’t know exactly how much cushioning would increase the impulse value, but I think it’s worth mentioning.

Hi, Sean,

Thank you for your comment. Here are some follow-up thoughts for you:

The definition of impulse in physics is change in momentum. Isaac Newton actually originally phrased Newton’s Second Law as force equals the rate of change of momentum with respect to time. The impulse, or change in momentum, in this scenario is really determined by the velocity of the foot going down versus the velocity of the foot coming back up (mass matters here too but you have a pretty constant mass over the course of a run). Using a cushioned shoe does change the time over which that impulse occurs, but that doesn’t actually change the impulse. In the same manner, when you get into a car accident, the airbag doesn’t really change the impulse or change in momentum your head undergoes (that is purely determined by the mass of your head and change in velocity). What a cushioned shoe does, or what an airbag does, is allow the change in momentum to occur over a greater time, and that reduces the force needed to make that change in momentum happen.

At first glance, if that is the only factor you look at, it seems like it would be a good thing; in fact, in the case of a car accident, it is! But imagine this scenario: If, upon the installation of airbags in cars, people decided to drive more recklessly and at much greater speeds, then people could totally undermine the benefit of the airbag by doing that. If they are driving faster, the impulse in a collision could be greater, and then despite the airbag extending the time over which the impulse occurs, you could end up with the same force or an even greater force.

So that seems to be what happens in cushioned running shoes. Imagine you are a barefoot runner to start with, but you are given a pair of very cushioned running shoes. You put them on and notice the force is less, so you start to run with a harder impact. Just like the airbags promoting reckless driving, the shoe can mask the fact that you are experiencing a greater change in vertical momentum with each foot strike, like you are driving faster now. Yet in Lieberman’s studies, barefoot runners experienced less force than shod runners—how is that possible? The key here is that the amount of impulse involved in a foot strike is set by three numbers: Mass, velocity on the way down, and velocity on the way up. You are the one that determines that, not your shoe. However, because cushioning allows the impulse to stretch out over a longer time, you experience less force, and then without that feedback, you start to change how you run so that you end up “recklessly” having a greater impulse in each stride and thus the forces get larger in the end. Sneaky, isn’t it?

There is a whole other facet of forces we haven’t even touched on, because the focus has been on the vertical forces. Another interesting chain of cause and effect with cushioned shoes is what goes on horizontally: Because the cushioning reduces the sensation of force, people that heel strike tend to reach out more in front of their bodies. If you freeze frame a video of a lot of runners, at impact their foot is in front of them, not under them (under is more typical of barefoot or minimally shod runners). Why does this matter? Newton’s Third Law says that if you exert a force on something, it exerts a force of equal magnitude on you, but in the opposite direction. If your leg is angled such that it is out in front of you at impact, it almost guarantees some degree of forward impact force on the ground, which means the ground pushes backward on you! That is the exact opposite of what you want to have happen. Imagine repeatedly tapping the brakes while driving and what that does to the smoothness of your ride, not to mention fuel economy! If you look at what the Pose method or Chi Running instructors teach, it is NOT to land with your foot out in front of you but more under you. It isn’t that the shoes make you reach out, but the cushioning lets you get away (at least in the short term) with reaching out because you don’t feel those forces as much. If you try reaching out in front of you with a heel strike when barefoot or minimally shod, you’ll either change your gait soon or hurt your heel. Again, the sneaky thing the shoe does here is not to make you run poorly but instead reduce the sensations that would have otherwise told you that you were running poorly.

Kind regards,

Marty Hughes, DC

I have a high-arched foot and have been told that cushioned footwear is important for this minority foot shape group. Are the “high archers” the exception to your thesis?

Hi, Adrian,

Thank you for your message. And thank you for your question. In short, high arches are no exception. Our philosophy is that most people are born with perfect feet and that any shoe that fails to mimic the natural shape of the human foot and/or prevents the foot from functioning like a barefoot inside the shoe is detrimental to long-term foot health.

Contrary to popular belief, the height of one’s arch is not the issue. What is essential, however, is the levelness of the foot’s support base and how closely the foot is able to interact with the ground. Please check out this article that helps to shed some more light on natural arch support:

www.naturalfootgear.com/blogs/education/17888744-natural-arch-support

I hope this info helps!

Kind regards,

Laura Trentman

What is the significance of the length of the primary arch relative to the length of the foot? For example, the length of the foot translates to a shoe size of 9, but the length of the arch suggests a shoe size of 11. I understand the impact on shoe sizing, where the arch length would not impact the shoe size in a flat-soled shoe, but does the longer relative length of the arch equate to a potentially stronger arch, or does its disproportionate size have negative impacts on other parts of the foot? Thanks!

Hi, Tim,

Thank you for your comment! In our experience, healthy arches come in a variety of lengths, heights, and widths, and having a relatively longer or shorter arch doesn’t necessarily correlate with positive or negative impacts on the rest of the foot, as long as the arch is able to function the way nature intended. For the main foot arch, this means that the entire foot is on a level surface and that there is adequate space for the toes to splay.

If you’re experiencing pain or weakness in any part of your foot, it could indicate the existence of another problem. If this is the case, consider scheduling an appointment with a local foot care practitioner to have your foot concern assessed.

I hope this has been helpful! I’ve included a link to a detailed article below that discusses natural arch support:

www.naturalfootgear.com/blogs/education/17920972-what-is-natural-arch-support

Cheers,

Andrew Potter

Thank you for your articles. I have started a new job in the last couple of months and have been trying to find good shoes for being on my feet, walking on concrete 8 hours a day. I have recently discovered what I believe to be a plantar fibroma. I have been researching, and your thoughts match up with what I have experienced. The so-called “walking” and “comfort” shoes are what seemed to cause the problem. I’m beginning to really pay attention to how my feet feel, and I now only wear shoes that allow my foot to function as though barefoot, or as close to that as possible. Thanks again!

Hi, Jan,

Thank you for your comment. We’re happy to hear that you’re finding our articles helpful.

If you need any help finding foot-healthy shoes for work or leisure, please just let us know. We’re happy to help out however we can!

Cheers,

Andrew Potter

I have fat pad atrophy. The bone-on-surface pain is excruciating. I MUST have cushioning, and more than most people.

Hi, Rie,

Thank you for your comment. I’m sorry to hear about your foot pain.

It’s certainly possible to experience fat pad atrophy, though sometimes folks are told that their fat pad has atrophied when, in fact, it’s simply migrated away from its original position under the metatarsal heads (due to the effects of conventional footwear). Determining if this is the case is important in knowing how to best address your foot pain.

In either situation (atrophy or migration), a metatarsal pad can be helpful in distributing body weight across the forefoot and reducing point tenderness. Flat, soft, foot-length insoles can also be helpful in reducing ball of foot discomfort.

For folks with true forefoot fat pad atrophy, some shoe cushioning can indeed be helpful in minimizing pain. We also recommend working with a local foot care provider on ways to reduce acute pain so that you can go about your daily activities in as little pain as possible.

I hope this info helps! Please do let us know if you have any other questions.

Kind regards,

Marty Hughes, DC

I have personally experienced the benefit of eliminating shoe cushioning (having had neuroma pain for years). Cushioned soles undermined my transverse arches, letting them collapse right onto the painful nerve. As soon as I got hard ground under my feet, the arches sprang up and the nerve was no longer being pressed upon.

Now I can walk as long as I like without foot pain. Most people can’t believe that the answer was to eliminate “support” from my shoes. But my feet do better with support from the ground!

Keep spreading the word!

Hi, Karen,

Thank you for your eloquent comment and for sharing your experience! I’m so glad to hear that your foot pain has disappeared. I wish you continued excellent foot health.

All best,

Marty Hughes, DC

I love the website and content. I have been following for years now and have ZERO NEUROMA PAIN. I do still have to use cushioned shoes for a couple of sports: tennis and squash. I also use cushioned Altra shoes for walking in the winter, but I notice a huge change in gait and muscle recruitment. I guess some people who live in our society just have to reverse how we use footwear. Mostly barefoot or tiny padding, and then padding when needed. Like safety helmets on jobsites, but not all the time. Keep up the great work!

Hi, David,

Thank you for your kind words about our site! Much obliged! Also, I’m so glad to hear that you’ve benefited from the adoption of foot-healthy footwear and that your neuroma-related pain has disappeared. That’s fantastic!

I think your safety helmet analogy is spot-on! Thank you for sharing that perspective with us.

All the best,

Marty Hughes, DC

I have a neuroma and a bunion on my left foot. My hiking boots cause extreme pain in the neuroma region. I have been looking for a wide toe box hiking boot WITH cushioning to protect against neuroma pain. I wanted to buy a Lems boot, but I was concerned about its relatively little cushioning. If I understand you correctly, perhaps I don’t need the cushioning, but the flat wide-toed boot instead? Thank you.

Hi, Grace,

Thank you for your comment. I’m sorry to hear about your neuroma and bunion. I will say, conventional hiking boots are notorious for causing (or exacerbating) all sorts of foot problems, something we delve into in greater detail in this article:

www.naturalfootgear.com/blogs/educational-articles/what-makes-for-a-great-hiking-boot

You may find that incorporating a metatarsal pad into a pair of wide toe box hiking boots (even if they have relatively thin soles) is helpful in addressing that neuroma-related pain or discomfort. Using Correct Toes toe spacers can also be a productive way to address both your neuroma and your bunion. I recommend that you view the following videos to gain a deeper understanding of the various natural approaches to resolving neuromas and bunions:

Neuromas: Conventional vs. Natural Approaches:

www.naturalfootgear.com/blogs/educational-articles/neuromas-conventional-vs-natural-approaches

Bunions: Conventional vs. Natural Approaches:

www.naturalfootgear.com/blogs/educational-articles/bunions-conventional-vs-natural-approaches

I hope this info helps! Please do let us know if you have any other questions we might be able to assist with.

All the best,

Marty Hughes, DC

For those of us living in semi-urban and urban environments, there needs to be a shoe designed to protect the foot if we land on a piece of glass or a pebble on a sidewalk. If you’ve ever encountered that pebble with a bare foot or very thin shoe, you know it can be agonizing and do serious damage. As a child, I went barefoot most of the time until my late teens, and my feet were much healthier. I would actually like to try these “toe glove” shoes if they: Had NASA-level sole protection—like very thin metal or nylon mesh, or something like it, to protect against grass, rocks, nails, etc. It would also be good to have a thin layer of artificial fat padding, since many of us seem to lose that by mid-life, of the kind that is used to make bike seat cushions, which I believe is silicone. There should be really thin cotton glove-like linings, so the feet would not stay soaked in sweat and grow fungi. Of course, I could run laps on an indoor rubber track, but it would be firm and 100% flat, taking away some of the benefits of natural footgear (not to mention the pleasure of being out in nature). How about it, shoe designers—can we have some of these shoes with extra safety and comfort features?

Hi, Perri,

Thank you for your comment. I hear your concern about stepping on sharp objects or debris while wearing thin-soled footwear, but in actuality, I think you may be overstating this issue. The foot—and the body as a whole—is really good at adapting to things it encounters, and most people are able to shift their bodyweight to avoid the unpleasant pressure or sensations associated with stepping on a pebble or road debris. In fact, one could argue that wearing thin-soled footwear offers the user a distinct advantage in this regard, as the increased tactile feedback that comes with wearing minimalist footwear leads to more conscientious footfalls and a lower likelihood of foot and musculoskeletal problems.

All the best,

Marty Hughes, DC

Hi. I work in a large warehouse store on concrete floors. My feet get too hot for most shoes. Would you recommend the ballerina flat for concrete floors? I am currently wearing Keen mary janes, which are fairly flexible, but they do have some padding, not really thick like some shoes do. Thanks so much!

Hi, Tierny,

Thank you for your comment. Though we certainly like the Ahinsa Ballerinas, you might find that a shoe such as the Lems Primal 2 is a bit better match for the workplace conditions you described. The Primal 2 has good ventilation, and the air-infused rubber sole offers your foot a comfortable environment upon which to rest. You can learn more about the Lems Primal 2 here:

www.naturalfootgear.com/pages/lems-primal-2-shoes

Cheers!

Marty Hughes, DC