For decades, we, as footwear consumers and users, have been told that we need plenty of padding in our shoes and under our feet to help boost comfort and buffer the forces on our bodies that occur during standing, walking, running, and jumping. Like many things in the health arena, this information has become common knowledge and accepted as fact. Shoe industry bigwigs along with countless healthcare professionals have championed this idea and instructed customers and patients to look for a high degree of padding or cushioning when selecting footwear, especially athletic footwear. Perhaps not surprisingly, the current ethos in the athletic shoe industry is to embrace padding and all its purported benefits, even going so far as to suggest that the so-called “maximalist” shoes now available are the next step in the evolution of optimal shoe form and function.

The lens through which we at Natural Footgear view footwear leads us to a very different conclusion about what constitutes truly foot-healthy footwear. This article is our attempt to debunk the idea that excessive shoe cushioning is in any way advantageous, and that it may, in fact, be detrimental to immediate and long-term foot and lower extremity health for many people. As always, we hope to cut through industry myths and provide you with the best possible information to make informed choices. Are we anti-cushioning? No, not per se; there are certain circumstances where some shoe padding may be helpful. What we do take issue with is the notion that more padding necessarily means a safer and healthier shoe for all. But more on this in just a bit.

The Myth

One of the main points we want to establish in this article is that there are a lot of misconceptions out there about shoe cushioning. The prevailing idea behind shoe cushioning is that a greater amount of padding under the foot will help reduce the impact forces on the body’s joints and tissues during weight-bearing activity. Intuitively, this may seem like a reasonable claim, given that we’ve been told for years that we need cushioning to protect our joints and soft tissues from damage. Indeed, it’s an easy concept to wrap our minds around. What you may be surprised to learn, however, is that physics and research do not support this claim. In fact, the more cushioning a shoe possesses, the harder and more damaging on our joints it may be.

The Physics

To understand why this is so, it’s important to understand the physics of collisions. To start with, the net force acting on an object is:

With a body that has one foot in contact with the ground, there are two vertical forces acting on the body, which are the ground pushing up, traditionally referred to as the Normal Force, which I'll write as N (normal in this context meaning perpendicular to the surface) and the force of gravity pulling down, often expressed as mg, or mass times 9.8 meters per second squared. So we have:

The acceleration is defined as change in velocity divided by time, so using vf as final velocity and vi as initial velocity, and doing some rearranging, we can write this equation as:

So what changes when someone goes from a thickly cushioned shoe to a minimalist shoe or even to being completely barefoot? The real expert in this realm is Professor Daniel Lieberman at Harvard, who has done some really nice studies on impact forces using force plates so that the forces of running shod versus barefoot can actually be quantified. But here is the essence of the argument: With shoe cushioning, our sense of what is going on is dulled (see Cushioning Issue #1 below for additional thoughts on this topic), and we tend to run with a certain gait—a gait that involves more up and down bouncing as well as feet that reach out more and strike first with the heel during the landing phase of walking or running.

There may be small fluctuations in the time that the foot is in contact with the ground between shod heel strikers and barefoot or minimalist midfoot strikers, which would affect the Normal Force, but the real key here is that the shod, cushioned gait makes both the initial downward velocity and the final upward velocity larger (Note: The above equation is written using the convention that up is positive and down is negative, so the vf is a positive number and the vi is a negative one—meaning when both numbers get larger, the difference between them gets larger). This results in a larger Normal Force, or, in other words, more force that the foot and rest of the body has to deal with. However, when running barefoot or in minimalist footwear, we tend to change our gait. We bounce less, and we tend to make the foot strike happen more underneath our bodies instead of out front. So, instead of landing hard on the heel like we do in cushioned shoes, we control the impact better in minimalist shoes or with our bare feet and make the difference between vf and vi less, thereby reducing the overall force on our feet and bodies.

Below are a couple of examples using real numbers in the force equation to illustrate the above points. For our examples below involving runners, let’s set mass (m) equal to 50 kg. The acceleration of gravity (g) is a constant at 9.8 m/s2. Let’s set the change in vertical velocity (vf - vi) equal to 8 m/s for cushioned shoes and 6 m/s for minimalist shoes or bare feet. For the impact duration, let’s use a value of 0.3 seconds for both cushioned shoes and minimalist shoes.

Note: To better understand the rationale behind the selection of these numbers, please scroll to the very bottom of this article, to the “Appendix: Understanding the Numbers” section, for a more detailed explanation.

Example #1: Force experienced by a runner in cushioned shoes:

Example #2: Force experienced by a runner in minimalist shoes (or with bare feet):

For the sake of comparison, a 50 kg person weighs 490 N in metric units of force, so that first number (for cushioned shoes) is about 3.7 times bodyweight whereas the second number (for minimalist shoes or bare feet) is only about 3.0 times bodyweight. Add that difference up over miles and days, months, and years of running and walking, and you can see why keeping shoe padding to a minimum makes such a huge difference.

It’s true that the physics of collisions is much more complex and detailed than what’s shown above (for example, we’re treating all of the person’s mass as moving up and down at the same speed; in reality, it’s more complicated as the torso obviously doesn't move up and down at the same speed as the feet do), but the equation does demonstrate the point that using cushioned shoes actually equates to greater forces on lower extremity joints and tissues, not less.

Note: If we wanted to get more technical in our calculations, we would take into consideration the fact that the ground reaction force is made up of several vectors in different directions. This would be a more rigorous way of explaining the force of the ground on the foot. The equation I used above captures only purely vertical force, which does make the point about vertical velocity changes in the foot being different between a heavily shod runner and a minimally shod or barefoot runner, but it leaves out the motion of the runner or walker and the foot itself in relation to the moving ground. Landing and takeoff angle would also be a factor here, as would the way in which force moves through the foot. And so on. The point is, though, a fancier model would still contain the key points demonstrated in the above examples.

Cushioning Issue #1: Joint Impact

What’s true of excessive shoe cushioning is that it’s highly deceptive: It makes us think we’re reducing joint impact because it feels that way, but in fact it’s just reducing the sensation of the impact. According to the laws of physics (as demonstrated above), the impact forces on our joints and tissues actually increase in more highly cushioned shoes. Excessive shoe cushioning can be hugely detrimental to our joints and tissues because it allows us to be sloppy with our footfalls or foot placement, and it allows us to slap our feet down with tremendous force without any perceived consequences.

When we fail to place our feet just right (including in the proper alignment relative to the ground), our weight distribution gets thrown off. The heels, toes, and arches are not able to properly absorb impact and distribute body weight. This can have negative implications for our feet, ankles, knees, back, and so on, all the way up the kinetic chain. By contrast, when we’re barefoot or wearing only thin-soled, flexible footwear, our feet and bodies can feel everything about the ground and what’s happening in our lower extremities. Footfalls tend to be gentler and more mindful, seeking out the smoothest path over which to move forward, and this can have a huge effect on the well-being of our joints and tissues.

Also, doing high-impact activities in shoes with no or only minimal cushioning can, in some cases, feel uncomfortable, but this isn’t necessarily a bad thing because it encourages a reassessment of how we’re performing an activity. Without shoes, landing on the heel can be painful and may result in larger than necessary collision forces. What tends to happen in barefoot people or people who adopt minimalist footwear is that, over time, they will actually develop the ability to move (walk, run, jump, etc.) in a less jarring way. Many people who use minimalist footwear or who go barefoot tend to spread their toes before striking the ground, landing first on the lateral (or outside) aspect of the ball of the foot and then rolling across the ball of the foot until the toe-off phase of gait, in which the big toe leaves the ground last. This footfall pattern, which also incorporates a foot strike that occurs more directly beneath the body's center of mass (instead of in front of it), helps reduce impact forces during the landing phase of gait.

So, interestingly, and perhaps unintuitively, often the best way for us to reduce joint impact is to reduce shoe cushioning. That said, this approach does require some time, patience, and care. And it tends to work best when our toes are splayed (ideally enabled by Correct Toes) and placed flat on the ground or on a completely flat sole, where each of our toes can bear their fair share of the weight. This development also tends to happen naturally; our bodies figure it out based on the strong tactile and proprioceptive feedback they experience in the minimally shod state.

Helpful Exercise: One illuminating exercise you can perform to observe the difference in impact forces between cushioned and minimalist shoes is to plug your ears and then go running, first in cushioned shoes, then in minimalist shoes. You should notice quite a difference in your ears right away, mostly in terms of the jolting and jarring forces your body experiences while running in cushioned shoes.

Cushioning Issue #2: Effort Expended

Another aspect of shoe cushioning that’s often overlooked is the fact that cushioned soles actually force us to do more work with each footfall. The greater the cushioning or sponginess in a given shoe, the less efficiently force is transferred between the foot (the big toe, really) and the ground. Energy that would otherwise go into propulsion is dispersed throughout the shoe’s padding and wasted. It’s a similar effect (though obviously less extreme) to running in sand. In people who ambulate in bare feet or in minimalist footwear, a maximum amount of propulsive energy is transferred between the foot and the ground during the toe-off phase of gait, and considerably less energy is wasted with each step or stride.

Cushioning Issue #3: Foot Muscle Atrophy & Arch Effects

Despite the fact that most conventional shoes, especially athletic shoes, possess springy cushioning under the foot, the relative thickness of the soles translates into greater sole rigidity, which can have detrimental effects on foot muscle strength and arch integrity. As has been said elsewhere on this site and around the web, wearing thickly-cushioned, rigid-soled footwear is like putting your foot in a cast and expecting it to get stronger. The relative foot immobilization that occurs in thickly padded shoes prevents foot muscles from doing their fair share of the work and allows them to slowly deteriorate, or atrophy, over time. A muscle that is not used regularly will lose its tone and its ability to generate sufficient force, which can have a significant effect on the function of the foot and the rest of the musculoskeletal system.

Shoes that possess no or only minimal padding and no built-in arch support help enable the foot to do what it’s intended to do (i.e., these shoes make the foot stronger, more flexible, and less susceptible to pain and stiffness). One of the first sensations many people experience after switching from conventional footwear with lots of cushioning to minimalist shoes with no or relatively little cushioning is the sensation of enhanced foot strength. Foot muscles that have long been underutilized begin to awaken, and the feeling of enhanced foot strength quickly becomes apparent. Shoes without excessive cushioning and so-called motion-control technology also help restore a strong and healthy medial longitudinal (ML) arch—the principal arch in our feet. I can tell you from personal experience that my own ML arch is now much more pronounced and defined since I adopted minimalist shoes and natural foot health techniques many years ago.

Cushioning Issue #4: Injury Frequency

One of the most frustrating aspects of the shoe cushioning debate is the notion that less cushioning inevitably means more foot and lower extremity injuries. A lot has been made of the class action lawsuit that was brought against Vibram FiveFingers, but the fact that Vibram settled their case does not suggest that minimalist shoes are injurious, only that Vibram may have gone too far in touting the health merits of their unique product. It’s true that injuries can occur when using minimalist footwear, but these injuries tend to be of the more acute (i.e., temporary) variety and most likely occur when users transition too quickly. Some problems, such as Achilles tendon issues, may be a direct result of the structural changes in the foot and ankle caused by conventional footwear worn over many years.

Indeed, conventional shoes make our feet weak, and so it’s likely that many people who experienced injuries using Vibram FiveFingers shoes weren’t ready to jump into this type of ultra minimalist shoe without a sufficient transition period. It could also be that users didn’t understand that the minimal cushioning was supposed to alter their gait, and that the altered gait is what most affects the equation shown earlier in this article and reduces forces on the body.

What’s easy to forget with all of the media attention surrounding Vibram FiveFingers shoes is that conventional footwear with excessive padding has caused literally countless chronic foot and toe problems over many decades, and that almost everyone who wears conventional footwear will experience some sort of significant foot problem at some point in their lives.

A classic study by Robbins and Waked published back in 1997 in the British Journal of Sports Medicine states the following:

Athletic footwear are associated with frequent injury that are thought to result from repetitive impact. No scientific data suggest they protect well. Expensive athletic shoes are deceptively advertised to safeguard well through “cushioning impact” yet account for 123 percent greater injury frequency than the cheapest ones.

The “cheapest ones” referred to above are shoes with the least cushioning and motion-control “technology” built into them. Robbins and Waked drew the following conclusions from their study:

This is the first report to suggest: (1) deceptive advertising of protective devices may represent a public health hazard and may have to be eliminated presumably through regulation; (2) a tendency in humans to be less cautious when using new devices of unknown benefit because of overly positive attitudes associated with new technology and novel devices.

Some may assume that shoes, especially athletic shoes, are designed by engineers or biomechanics experts to optimize movement while maximizing foot comfort and health. But the reality is that the shoe industry is driven by aesthetics, or by what “looks good” on the shelf, and that little attention and resources are devoted to creating truly foot-healthy products. So, the very shoes that are touted to enhance athletic performance and prevent injuries actually hinder performance and cause injuries by altering natural foot form and function as well as gait. Indeed, nature gave us everything we need to ensure lasting foot health and prevent injuries, as evidenced by this passage from a study published by Michael Warburton in the journal Sportscience:

Running barefoot is associated with a substantially lower prevalence of acute injuries of the ankle and chronic injuries of the lower leg in developing countries [...] Laboratory studies show that the energy cost of running is reduced by about 4% when the feet are not shod.

While going barefoot is not for everyone, finding shoes that allow the foot to act like a healthy bare foot inside the shoe is something that almost all of us can do to ensure long-term foot and lower extremity health, especially now that natural footgear exists to enable this foot health behavior.

Cushioning Issue #5: Knee Problems

Another important consideration in the shoe cushioning debate is the effect of footwear on knee health. When we land on our heels (as almost all runners and walkers who wear cushioned shoes do), our arches and ankles can't help as much in managing impact, so our knees and hips have to handle our bodies’ natural shock absorption. However, as mentioned earlier in this article, barefoot or minimally shod runners tend to adopt a gentler, impact-mitigating midfoot strike, allowing the arches and ankles to contribute better to shock absorption. With more joints handling the shock, the forces get more evenly distributed between the lower extremity joints.

The relationship between padded shoes and knee problems (specifically, knee osteoarthritis) has been examined more closely in recent years. Conventional medical wisdom states that the following factors may contribute to knee osteoarthritis: Weight, heredity, gender, age, previous traumatic knee injuries, repetitive stress injuries, participation in contact sports, certain health conditions, nutritional deficiencies, and physical deconditioning.

While many of these factors undoubtedly contribute to an accelerated rate of articular cartilage loss, the role of conventional footwear in the development of knee osteoarthritis is perhaps the single most important factor in the onset of this health problem. Several reliable and credible sources have produced compelling arguments linking the long-term use of conventional footwear (i.e., padded shoes with tapering toe boxes, toe spring, heel elevation, and relatively rigid soles) with the development or worsening of knee osteoarthritis.

A 2006 Rush Medical College study, conducted by Najia Shakoor and Joel A. Block and published in the journal Arthritis and Rheumatism, examined stress loads on the knees of study participants who wore various shoe types and no shoes at all. The researchers state the following:

It appears that patients with medial knee [the inside aspect of the knee] OA [osteoarthritis] undergo significant reductions in joint loads at their knees and hips when walking barefoot compared with when walking in their normal shoes. Since knee OA is mediated in part by aberrant loading, and since excess loading has been shown to be associated with pain and disease progression, these data suggest that modern shoes may exacerbate the abnormal biomechanics of lower extremity OA.

Shakoor and Block conclude that:

Shoes may detrimentally increase loads on the lower extremity joints. Once factors responsible for the differences in loads between with-shoe and barefoot walking are better delineated, modern shoes and walking practices may need to be reevaluated with regard to their effects on the prevalence and progression of OA in our society.

It's my personal belief, and clearly the belief of the researchers above, that a lot of lower extremity osteoarthritis could be avoided if we were more selective and judicious with our footwear choices.

Harnessing the Natural Protective Mechanisms of Feet

Individuals who have gone barefoot or who have worn minimalist footwear their entire lives possess several built-in mechanisms that offer sole protection. The first of these mechanisms is optimal toe splay. Toes that are splayed well apart confer a large degree of protection from the impact forces experienced during weight-bearing activity by spreading the impact forces out over a larger surface area. Conventional shoes force the toes together and elevate the toes above the forefoot, focusing a majority of the impact forces on a much smaller area of the ball of the foot. Correct Toes toe spacers can be worn inside shoes with a sufficiently wide toe box to help restore natural toe splay and disperse impact forces over a larger surface area of the foot.

SHOP CORRECT TOES

Our feet also possess several plantar fat pads (under the toes, ball of foot, and heel) that help naturally absorb impact forces, assuming that these pads are positioned properly. In individuals who have worn conventional footwear for years or decades, the forefoot fat pad that’s intended to provide protection for sensitive ball of foot structures becomes displaced anteriorly (i.e., toward the ends of the toes) due to a shoe design element called toe spring. This displacement leaves ball of foot structures (e.g., nerves, joint capsules, bones, etc.) vulnerable to the large forces incurred by the body during weight-bearing activity and can cause or make worse conditions such as neuromas, capsulitis, and stress fractures.

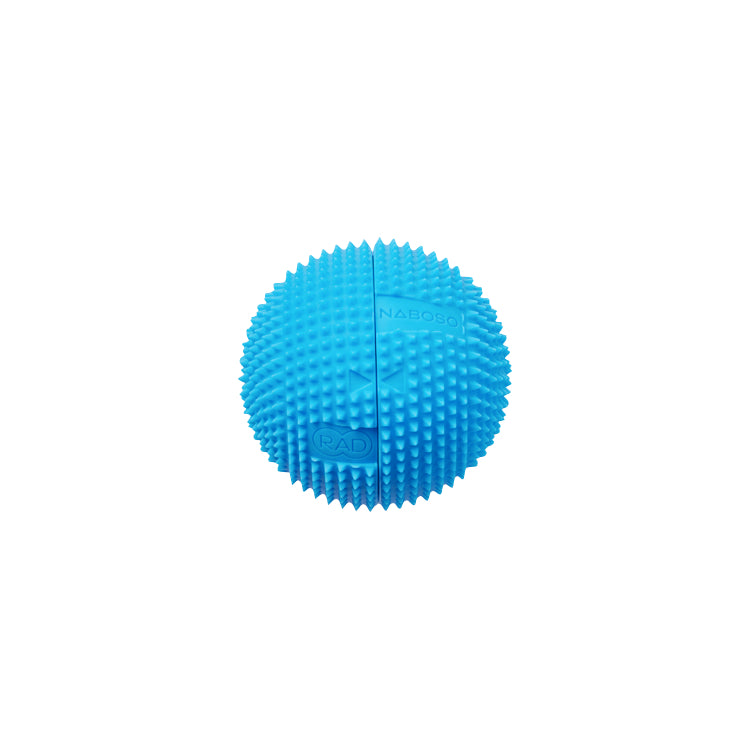

In those transitioning from conventional footwear to minimalist or minimalist-like footwear, three key pieces of footgear can be helpful in eliminating discomfort, restoring fat pad position, or augmenting the natural shock absorbing abilities of the plantar fat pads: Pedag metatarsal pads, Naboso insoles, and Tuli’s heel cups.

SHOP PEDAG MET PADS SHOP NABOSO INSOLES SHOP TULI'S HEEL CUPS

Of all the natural protective mechanisms built into our feet, perhaps the most important is the ML arch. Our foot arches, including the ML arch, are natural shock absorbers and are designed, like arch bridges, to bear an incredible amount of weight. In fact, our foot arches are at their best when they are loaded, as this causes all arch components—bones, ligaments, tendons, and other tissues—to mesh to a greater degree.

Note: Many of the bones in the foot are themselves arch shaped, suggesting that these bones are perfectly designed for bearing weight.

But in order to help stabilize the foot and ankle and absorb shock, the ML arch needs to be on a level and stable support platform. Most conventional shoes, from casual shoes to athletic shoes, possess a spongy or springy sole that elevates the heel above the ball of the foot, which in turn acts to destabilize the main foot arch and reduce its ability to effectively absorb and disperse impact forces. Shoes with minimal cushioning and a completely flat support platform help manage impact forces by enabling natural arch support, strengthening the foot’s arches, and creating a situation of optimal stability in the foot and ankle complex.

Might Some People Benefit from Cushioning?

Some of you reading this article may contend that shoe cushioning is essential for foot comfort. And that may indeed be true, especially for individuals who have experienced some sort of foot trauma. However, it’s likely that most people who rely on conventional shoes with plenty of built-in cushioning for foot comfort have done so for many years, perhaps decades, and that their feet have adapted to the environment in which they've been confined.

Jumping immediately from cushioned shoes to shoes with relatively little cushioning is not necessarily the right thing for everyone. In fact, a slow and measured transition period is extremely important. This article discusses possible ways to transition to more minimalist-like shoes in a safe and stepwise manner and is particularly relevant for people who have long worn conventional footwear. Adopting a transitional shoe—a flat-soled, wide toe box shoe that possesses a moderate degree of cushioning—before a true minimalist shoe is one approach that many people have benefitted from.

Shoe Cushioning: An Impediment to Optimal Foot Health

The intention of this article is to put the role of shoe cushioning into proper perspective and to examine the ultimate value of shoe cushioning as a foot health and injury prevention tool. Hopefully this article has presented a new viewpoint on the utility of shoe cushioning or perhaps confirmed your suspicions about the claims of many shoe manufacturers. In our experience, we have found that shoe cushioning (especially excessive cushioning) is often an impediment to optimal foot health, and that true foot comfort can be achieved, in many cases, by restoring proper foot and toe anatomy and alignment through the use of helpful and unobtrusive natural footgear.

How comfortable a shoe feels is not in itself a good criterion for predicting long-term foot health or even success with a particular shoe. There are a lot of factors to consider when selecting foot-healthy footwear, including making sure that it fits correctly and taking the time to transition properly. When it comes to choosing the best footwear to put on your feet, exercising care and good judgment is always the best policy. To learn more about the best footwear options for you and your unique foot needs, consider speaking with a naturally-minded foot health expert, or check out our foot-healthy footwear options for men or women.

SHOP MEN'S SHOES SHOP WOMEN'S SHOES

Appendix: Understanding the Numbers

In conducting online research for this article, I found several references for the duration of ground contact that suggested 300 milliseconds (or 0.3 seconds) for the average runner, all the way down to 0.2 or even slightly less for more elite runners. This number seemed to be about the same for both shod heel strikers and barefoot midfoot strikers.

In trying to determine accurate values for the change in vertical velocity of the foot between the heavily shod and the minimally shod, other factors needed to be considered, including cadence and the distance traveled by the foot per stride. Allegedly, an average runner has a cadence of 160 strides per minute, getting up to 180 for more experienced runners. An estimation of the vertical distance the foot goes up in one stride is 0.35 m to 0.4 m. If you double that distance (going up plus going back down), multiply by 160, and divide by 60 seconds, you can determine that the average speed of the foot during a stride has to be around 2 m/s.

The tricky part here is that the foot isn't going at a constant speed; it is paused for a moment at the very top as it transitions from going up to coming back down. It’s paused again while in contact with the ground. The simple way to estimate the top speed of the foot is to just double that number, so say 4 m/s on the way down right before impact, and 4 m/s on the way up right after losing contact with the ground. That would give a change in velocity of 8 m/s. Those numbers are based on runners wearing cushioned shoes, so it seems accurate enough to use a value of 6 m/s for minimally shod or barefoot runners.

A very special thank you to physics instructor Peter Peterson and mechatronics engineer Dan Casciato for their kind assistance with various aspects of this article, especially the physics section.

If you look at the foot of a young child, you will notice that his or her toes are spaced well apart. The foot of a young child is naturally designed for optimal balance and gait, and if the foot maintains this shape, optimal stride is preserved through old age: a finding observed in barefoot populations the world over. In industrialized societies, however, people spend a lifetime wearing shoes with...

Read more

If you look at the foot of a young child, you will notice that his or her toes are spaced well apart. The foot of a young child is naturally designed for optimal balance and gait, and if the foot maintains this shape, optimal stride is preserved through old age: a finding observed in barefoot populations the world over. In industrialized societies, however, people spend a lifetime wearing shoes with...

Read more

I am 68 and have many foot problems that all seem to have developed “overnight.” I have fat pad atrophy, two neuromas on my right foot, ball of foot pain, and a hammertoe on both feet. I am under the care of a podiatrist who wants to do surgery on the neuromas (after me already receiving cortisone shots). This will not help the fat pad atrophy, but I thought it would at least help with some pain. The first podiatrist I saw had me buy expensive orthotics, which did not help. I have not been able to find sneakers that feel good, and I wonder if you could recommend a pair that would feel good and also any other products that would help my foot problems? I did try the Altra sneakers and they were great for the toes but did not have enough support and hurt my feet, which I am assuming was because of the fat pad atrophy. Any help would be most appreciated.

Hi, Barbara,

Thank you for your comment. I’m sorry to hear about the multiple foot challenges you’re facing. I’d like to share with you several foot condition-related resources from our site that I think you might find beneficial:

Neuromas:

www.naturalfootgear.com/blogs/educational-articles/neuromas-conventional-vs-natural-approaches

Ball of Foot Pain:

www.naturalfootgear.com/blogs/educational-articles/ball-of-foot-pain-conventional-vs-natural-approaches

Hammertoes:

www.naturalfootgear.com/blogs/educational-articles/hammertoes-conventional-vs-natural-approaches

In addition to the above resources, here are two more articles that I think you’ll find helpful in your journey toward optimal foot health:

www.naturalfootgear.com/blogs/educational-articles/10-best-natural-foot-health-tools-tips

www.naturalfootgear.com/blogs/educational-articles/how-to-shop-for-shoes

Please give the above videos and articles a look and let us know if you have any additional questions!

All the best,

Marty Hughes, DC

Do feet widen as we age? Are they supposed to? When I was a young man, I was told I had a narrow foot. Therefore, I always bought shoes that were narrow or B width. I now wear D width shoes, but even with going to more width, I have had nothing but trouble with my feet over the years (left big toe bunion, callus on the right side of my left big toe, right little toe pain, neuromas on both feet, intermittent blisters on both soles in various places). But wider shoes still have a toe box that squeezes the toes. I assume that is a large part of my problems. However, I think a lot of people are concerned that going to a VERY wide toe box might feel good on the toes, but might be TOO wide and will eventually result in more problems because there’s simply TOO much room for the foot to slide around in. In other words, the shoe might ultimately be TOO big for them. Won’t wearing a shoe that’s too big in the toe box cause problems, too?

I am also concerned that wearing Correct Toes INSIDE my shoes when exercising will only make the callus on the right side of my left toe even worse, as well as the pain in my right little toe. I’m currently considering getting some Lems Primal 2s, but I am concerned that going to such minimalist footwear will only make my plantar fasciitis worse. I also have pain on the back right SIDE of my right heel, which doesn’t seem normal to me. I know I have PF, but I also have the heel pain on the side of my right foot. Some people have so many foot problems, they don’t know where to start. I have a set of orthotics that were very expensive and made by a podiatrist. I know you generally don’t like orthotics, but it’s one of the few things that make my feet feel better when walking. I’ve tried all sorts of insoles that are supposed to be helpful for various problems, but they all just seem to make the problems worse. And most podiatrists do, too! Most podiatrists disagree with the stuff you’re preaching. So what are people supposed to do? You recommend people go to a “foot specialist,” but they are part of the problem! They recommend the things you’re against.

Hi, Joe,

Thank you for your comment. And thank you for your questions. I think a lot of us would be surprised by the true width of our feet, if our feet had been allowed to develop without the constricting effects of conventional footwear. Many peoples’ feet do indeed begin to widen out over time after adopting the natural foot care approaches discussed on this site, and that’s a sign of positive changes afoot!

To your question about some wide toe box shoes possibly being too wide and causing problems as a result, I would say that this is usually a non-issue and that the more room the toes have to roam free, the better. I say it’s a non-issue because footwear is usually secured at the level of the ankle, and so there is only so much forward shifting of the foot that can occur in most shoes or boots (typically, very little or none at all). Also, most wide toe box shoes fit pretty snugly throughout the instep, which helps minimize any side-to-side shifting of the forefoot inside the shoe.

In terms of your concerns about adopting minimalist footwear, my recommendation is to simply take it slowly and monitor your feet closely! You might appreciate the info contained in this article from our site that discusses how to successfully transition from conventional footwear to minimalist footwear:

www.naturalfootgear.com/blogs/educational-articles/how-to-transition-to-minimalist-shoes

When it comes to sourcing a foot care professional in your area, it can indeed be challenging to find someone who is naturally-minded. With that in mind, we put together a resource on our site that lists some of the most important interview questions to ask any prospective foot care provider before your first in-person visit (to help get a sense of how a given provider’s foot health philosophy might mesh with your own). You can find that resource here:

www.naturalfootgear.com/blogs/popular-q-a/what-questions-should-i-be-asking-a-prospective-foot-care-provider

I hope you find this info helpful, Joe! We’re here if any additional questions arise.

All the best,

Marty Hughes, DC

I was born and raised in India, where everyone wears flip-flops at home. Back home, I never heard of conditions like plantar fasciitis, Morton’s neuroma, etc. I never wore cushioned sneakers growing up, and it’s only after moving to the US that I noticed “cushioning” being considered of the utmost importance. I got a labrador and started going for several long walks a day, and I felt my ankle and feet were losing their strength due to all the cushioning in the shoe. I could not feel the ground I was walking on, and this completely altered my stride. After 6 months, I woke up with severe pain and had to ice my feet every 30 mins just to make it through the day. I couldn’t walk my dog anymore, and I was housebound, lying on the couch for hours due to being in so much pain. This led to me researching footwear issues, and I concluded that my cushioned shoes led to this disaster. I love the feel of Converse sneakers, as I can “feel” the ground when I walk, but they are too narrow for me and don’t allow me to spread my toes.

A visit to the podiatrist led me to buy stability shoes, and they feel like a concrete block on my feet. They left indentations on my feet near the heels, and I will not be wearing them. I don’t know how stability shoes are the answer. The podiatrist blamed everything on genetics and said nothing is in my control. Also recommended were custom orthotics for $1,300, which my insurance will cover, but which I refuse to get. My feet served me well before, and if I strengthen them as well as my core, including glutes and hips, they will continue to work well for me. I was completely put off by the “podiatrist-recommended” shoe selection at the store, which consisted solely of models that incorporated extreme cushioning. I believe the foot can handle the stress placed on it from walking or running, as long as the shoes are appropriate. I am going to buy a shoe with a wide toe box, preferably canvas. I am tired of cushioned shoes. I might go minimalist, but I will transition slowly, over months. I do not run on pavement, or on any other surface, for that matter, so it will suffice for my walking needs.

Hi, Divya,

Thank you for sharing a bit about your experience with conventional foot care approaches. Unfortunately, what you’re describing is a fairly typical scenario, and it’s a perspective and methodology that often fails to consider the true underlying cause of most foot and toe problems. Take heart, though, that alternatives exist, and that’s what we explore and discuss on the Natural Footgear site! If you ever have any questions about natural foot health concepts and approaches, please don’t hesitate to reach out; we’re here to support you however we can!

Kind regards,

Marty Hughes, DC

You could go back to some of the earliest research on this topic by Robbins. His work in 1988, which was titled “Sensory Attenuation Induced by Modern Athletic Footwear,” was what started me on my doctoral work. Incidentally, my early work on this topic was what won me the NATA doctoral dissertation award, in 1998, and led to this publication: “Athletic Footwear, Leg Stiffness, and Running Kinematics.”

Thank you for your comment, Paul! It’s always nice to hear from one of the pioneers in this field of research!

All the best,

Marty Hughes, DC

Hello. I am a student at Brigham Young University and am currently working on a literature review surrounding the correlation between shoe cushioning and foot health. I was wondering if you could tell me when this article was written so I can accurately cite it in my paper? Thank you for your time and help!

Hi, Bradley,

Thank you for your question. This article was published on our site in June of 2015. Please do let us know if you have any additional questions about the article or the topic of shoe cushioning and foot health. Good luck to you with your literature review!

All the best,

Marty Hughes, DC

I did fast-read this interesting article, but I may have missed something that is currently making me think. I’ve run in Vibram FiveFingers for 10 years and love them, and I have no intention of stopping. My only thought as a 5K racer is the following: Are cushioned running shoes faster? I’ve no intention of going full-blown platform cushioning, but I’m curious about some thicker-soled models if they are faster.

Hi, Laurence. Thank you for your question! It’s an interesting one to consider, as it frequently comes up when the merits of minimalist vs. maximalist shoes are debated. If you’re accustomed to road racing in your Vibram FiveFingers and have been doing so for a decade, you’ve no doubt built up an incredible amount of foot strength and stamina. With the kind of ultraminimalist footwear you run in, you’re drawing upon the natural elastic properties inherent in your foot and lower leg tissues to propel you forward at a speed that is, no doubt, sustainable for your musculoskeletal system, including (perhaps most importantly) your joints.

It could very well be possible that a more padded shoe will permit you to run faster, but it’s most likely not because of the springiness of the material beneath your foot, but rather because the padding allows you to blow right past any warning signals your body might be sending you about the effects of the increased speed or impact on your muscles, tendons, ligaments, bones, and joints (which is not always obvious in the moment). It’s also important to consider the energy drain that comes with the spongy materials incorporated into the outsole of more padded athletic shoes. Energy that would otherwise go into forward propulsion is dispersed throughout the shoe’s padding and wasted, forcing you to do more work with each footfall.

So, if you’re already adjusted to the experience of racing in minimalist footwear—and it sounds like you are—then our recommendation would be to stick with that and try improving your race times through other possible avenues (training, recovery, form, diet, sleep, etc.). We hope this info helps! Please don’t hesitate to reach out with any follow-up questions.

Yours in Foot Health,

Drs. Marty & Robyn Hughes

I have osteoporosis (and cachexia), and I am curious to know if there are studies concerning walking barefoot as a way to increase the impact on the calcaneus, which I heard is a stimulus for bone deposition. I have a history of falls and fractures. What can you advise?

Hi, Jeanne,

Much appreciation for your comment. Barefoot walking can certainly have benefits for bone health! The impact from walking barefoot can help stimulate bone deposition in the calcaneus (heel bone), especially if you gradually increase your exposure. However, given your history of falls and fractures, it’s important to start slowly and consider any safety precautions (e.g., walking on a flat, safe surface) to avoid additional risks. If you’re interested in more personalized advice, it might be helpful to consult with a foot care specialist who can help guide you based on your specific health conditions. Foot strengthening exercises could also be beneficial for increasing bone density.

All the best,

Marty Hughes, DC

I am almost 66 years-old. When I was much younger, I could wear shoes without worrying about extra padding. But it is a fact that as one ages the padding under the foot goes away. You could say that too much padding might make shoes too tight, which would not be good or healthy. But I really need padding around my toes even with flats now. Even the side of my big toe needs padding now. That is just how it is when one ages.

Hi, Barbara,

Thank you for your comment. Padding can indeed help ease discomfort in some cases and circumstances, especially around sensitive areas like the big toe. In your case, it’s important to find shoes that allow for both sufficient cushioning and proper toe space to avoid tightness around your forefoot. Consider looking for wide toe box shoes with removable insoles so you can add extra padding as needed without sacrificing fit. Every set of feet is unique, and it’s great that you’re being proactive about seeking both foot health and comfort from your footwear.

Kind regards,

Marty Hughes, DC

Hi. I have corns on my feet. I’ve tried all different types of shoes, but I’m still having problems. Also, I have used soft-cushioned shoes, but I think they caused me to develop more corns and pain under my feet. Can you suggest which type of shoes I should buy? Thanks.

Hello, Bhavik,

Thank you for your comment. I can appreciate that corns can be really frustrating, and it sounds like you’ve been trying a lot of options. It’s good to focus on shoes that allow for ample toe space and avoid any friction or pressure. Look for shoes with soft, flexible uppers and a wide toe box that doesn’t pinch or squeeze your toes. You might also want to experiment with soft gel pads or moleskin around the corn areas to minimize irritation.

All the best,

Marty Hughes, DC

I have an issue where my femurs are internally rotated, so there is a constant torque on my knees, and I have tons of knee pain. Wearing custom orthotics that keep me from pronating due to the rotation of my femurs and well-cushioned sneakers has helped my knee pain. Do you think such cases might call for cushioning and orthotics? Or even in these kinds of cases, would theory suggest that no cushioning (and/or no orthotics) could still be best? Thanks so much!!!

Hi, Asher,

Thank you for your comment. I’m glad to hear that you’ve been able to find some relief from your knee pain. Our general approach is that, if something is working well for you, it’s probably best to stick with that. I will say, though, that adopting wide toe box, zero-drop shoes with some cushioning, like Altra shoes or certain models of Topo Athletic footwear, might provide you with some additional musculoskeletal health gains without negatively impacting the improvements you’ve seen in your knee pain. This is an important conversation to have with your foot care provider, though.

Here’s wishing you much continued success on your journey toward optimal alignment and pain-free living!

All the best,

Marty Hughes, DC